That is the question asked by a 2022 NBER working paper by Pierre Dubois, Ashvin Gandhi and Shoshana Vasserman.

Methodology: Demand Side Model

The authors used IQVIA data on revenues and quantities of drugs sold to hospitals from 2002 to 2013 across US, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and UK markets. The authors define a market based on the Anatomical Therapeutic and Chemical classification (ATC-4) level to account for the possibility of drug substitutes for treating similar diseases. They then create a representative consumer demand model estimating indirect utilities relative to an outside good (i.e., no drug purchase). Drug characteristics include the drug’s molecule identifier, patent status and generic status. Heterogeneity is modelled using random coefficients for differential utility of the product, differential disutlities from higher prices, and differential preferences for brand vs. generic drugs. The demand model is estimated using a our demand model according to the standard BLP method with instrumental variables for prices. The specific instrument used is the number of products in the same ATC‑4 class, the number of generics and off‑patent brands, and the number of countries in which the drug is sold. This helps to set price as a function of competition as demand is likely a function of price; competition level likely do not impact demand significantly except through price and thus make a reasonable instrument in this case. Although the authors have data from multiple countries, the demand model is estimate for US and Canada.

Methodology: Supply Side Model

The authors model equilibrium price setting using a Nash bargaining model. In the model, firms maximize profits while government regulators maximize consumer welfare. Canada bargaining is modeled as a single payer entity; US negotiation and price setting is assumed to occur through Bertrand competition. Negotiation occurs market by market (i.e., at the ATC-4 level).

Results

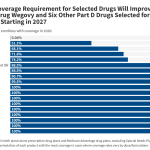

International reference pricing is likely not to have a material impact on US prices but would greatly increase prices in Canada.

In the main specification, an international reference pricing policy where the price in the US cannot be higher than in Canada, Canadian prices become effective price ceilings for the same drugs sold in the US. This constraint binds when firms negotiate prices with the regulator in Canada, but the effect on reducing expenditures in the US is relatively small. Moreover, we find that while baseline reference pricing decreases prices a bit in the US, it increases prices dramatically in Canada because the firms’ disagreement payoff in negotiations becomes tethered to unconstrained US profits. Expenditure on pharmaceuticals therefore increases considerably in Canada but does not change significantly in the US.

What happens if the number of countries in the reference basket changes? Still, US prices only decrease modestly.

…referencing an index of countries or increasing the size of the country being referenced both lower equilibrium prices for US consumers. However, the price reductions are surprisingly small relative to the status quo price differences between the US and Canada. A key reason is that US market is so unrivaled in its size that even when referencing larger countries or more countries, profitability in the US market still drives negotiations in the referenced country/ies rather than the other way around.

You can read the full paper here.

Appendix: BLP method explained.

The BLP method (Berry–Levinsohn–Pakes) is a structural approach for estimating random‐coefficient discrete choice demand models for differentiated products. It combines:

A random‐coefficients logit (or other discrete choice) utility specification over products,A nonlinear “inversion” from observed market shares to mean utilities, and thenInstrumental variables (IV) estimation of the demand parameters, treating prices as endogenous

In practice, the BLP estimator is a nonlinear IV–GMM that:

allows flexible substitution patterns,allows preferences to be random, andhandles price endogeneity via instruments that shift prices (e.g., cost shifters, BLP-style instruments based on rivals’ characteristics)