Last week, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released a report titled “How Changes to Funding for the NIH and Changes in the FDA’s Review Times Would Affect the Development of New Drugs.” The report evaluates two scenarios:

A permanent 10 percent reduction in the amount of funding that the government provides to the NIH, andA nine-month increase in the time it takes the FDA to review new drug applications (NDAs).

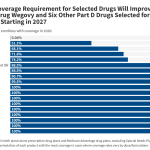

CBO estimated that a reduction in the NIH’s funding of external preclinical research would ultimately decrease the number of new drugs coming to market by roughly 4.5 percent, or about 2 drugs per year. That result would not be immediate; rather, the impact of the reduction in funding would grow over a 30-year period and would take full effect in the third decade after the reduction began.

Why does drug development go down? The answer is that basic research (e.g., NIH funding) and clinical research (clinical trials) are complements. Basic research identified more promising candidates for clinical trial testing. One study (Cleary et al. 2018) found that “>90% of NIH funding relates represents basic research related to the biological targets for drug action rather than the drugs themselves.” Moreover, Zhou et al. 2023 found that “NIH spending on clinical development focuses on early-stage trials, representing a small fraction of estimated industry spending.”

Why does it take so long for this effect to occur? Drug development timelines are long. Thus, cuts to NIH funding won’t impact drugs currently undergoing clinical trials. However, there will be fewer promising targets for clinical trials in the future with reduced NIH funding.

Delays in FDA approval timelines also negatively impact drug development. The CBO report states:

A nine-month increase in FDA review times for NDAs would reduce the number of FDA approved drugs in the first year following the increase because all but three months’ worth of drug approvals would shift to the next year. In addition to that initial delay, the increase in review times would reduce the number of such approvals by raising the cost to develop new drugs. The number of drug approvals deterred by the increase in development costs would grow over time and would reach its full effect of a2 percent reduction—amounting to about one less new drug—each year in the second decade after the increase in review times began.

Methodology

How did CBO come up with these numbers? They used their simulation model of new drug development. That model assumes that:

A 15 percent to 25 percent reduction in expected returns for drugs in the top quintile of expected returns is associated with a 0.5 percent average annual reduction in the number of new drugs entering the market in the first decade under the policy, increasing to an 8 percent annual average reduction in the third decade.

A 2025 USC report, however, argues that the elasticity of innovation used by CBO is too conservative.

First, the CBO’s model restricts attention to the decisions to begin Phase 1, Phase 2 and Phase 3 clinical trials, and policy changes are assumed to have no impact on preclinical discovery

research. In contrast, in Filson’s model, policies have their most substantial direct impacts on discovery research…Second, the policy considered by Adams is assumed to impact only those firms whose expected present values of product-market profits lie in the top 20% of the distribution of expected present values of profits. Real-world policies do not target firms this way because it is not feasible to do so: Real-world policies directly impact prices or revenues

rather than profits..

There are additional critiques, but the USC white paper would argue that the CBO’s estimate is a relatively conservative one with respect to how reduced NIH funding and longer FDA review times impact drug development.

You can read the full CBO report here and the simulation model methodology is here.